At 10 pm in the evening of yesterday, twenty-fourth of the current month, the excavation site at Pompeii was struck by three bombs during an aerial bombardment of nearby towns in the Vesuvius area: one bomb fell on the Forum area, another on the house of Romulus and Remus, causing considerable structural damage; a third bomb fell on the Antiquarium, with serious damage to archaeological material, which is only partially salvageable. In view of the continuation and intensification of aerial attacks in the area, I believe it is necessary to call for intervention by neutral countries to prevent the blinkered and brutal violence that threatens to destroy Pompeii, an inviolable monument to all human civilization. Visiting the site in person, I ascertained the damage and took remedial measures. I applaud the exemplary conduct of the night watch staff.

(Phonograph recording of of Superintendent A. Maiuri speaking to the General Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts, Pompeii 8/25/1943).

During the Second World War, between August and September 1943, the archaeological area of Pompeii was bombed by Allied forces, with the aim of accelerating the retreat of German troops. About 170 bombs were dropped by British and Canadian bombers, hitting and damaging several points of the excavation area.

Only recently have the literature and the scientific community paid due attention to these dramatic events, which constitute a fundamental watershed in the modern history of the site.

The threat of military action had been warned of for some time, as we can read in the words of the then Superintendent Amedeo Maiuri who, particularly between late 1942 and mid-1943, had sought to raise awareness of the risk of harm to the archaeological heritage on the one hand and, on the other, had accelerated the protection of buildings and moveable items, some of which were moved to the Archaeological Museum of Naples and Montecassino Abbey.

Boxes of bombed bronzes selected for conservation: from D. Elia, V. Meirano (a cura di), “Pompeiana Fragmenta. Conoscere e conservare (a) Pompei. Indagini archeologiche, analisi diagnostiche e restauri”, Torino 2018, fig. 3, p. 241 (© V. Meirano)

“In Pompeii there is no time to waste. As much to fear as the first impact of the invasion are the bands of roaming thieves and bandits seeking to plunder abandoned or damaged houses. Statues were removed from the gardens of the houses of the Vettii, the Amorini, Marcus Lucretius and Loreius Tiburtinus and the herms of Vestorius Priscus and Holconius Rufus, and everything was buried and walled in the hypogeum of the Stabian Baths, under the protection of the mofette, and that was excellent advice. But who will save monuments, houses and paintings from the fury of the bombardments?”(A. Maiuri, Taccuino napoletano, Naples 1956).

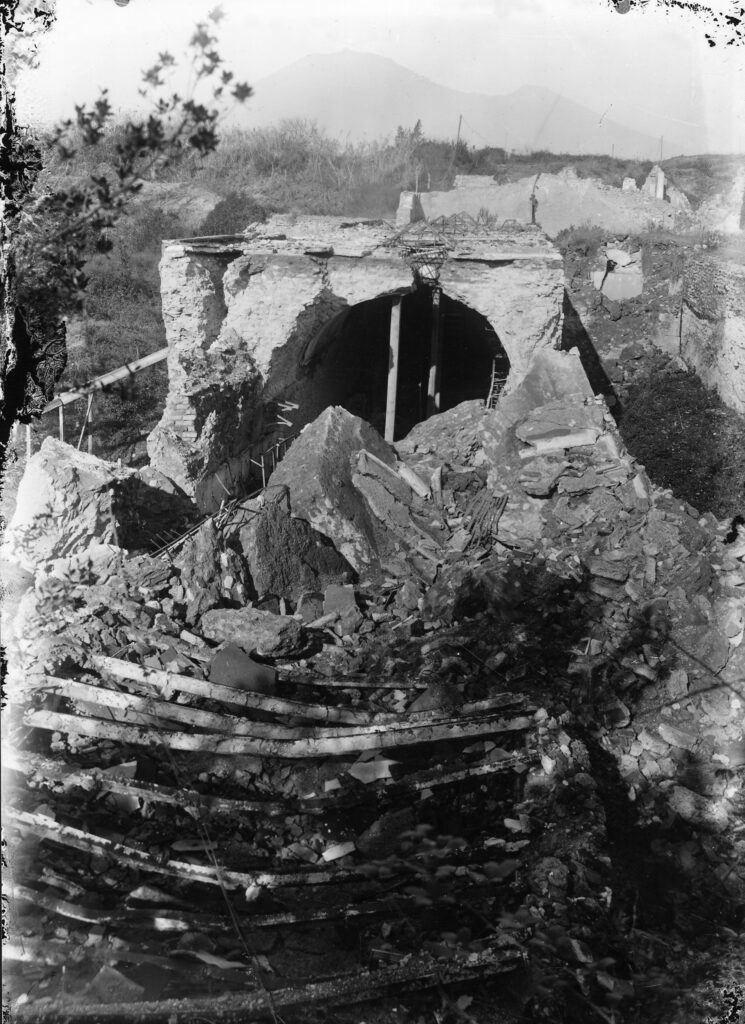

House of Romulus and Remus (VII, 7, 19) after the bombing

At the beginning of summer 1943 the likelihood of safeguarding the excavations was becoming increasingly uncertain and the threat of an attack increasingly imminent; from mid-July onwards, heavy bombing struck the city of Naples and the surrounding areas. At the time there was also a widespread opinion that the archaeological site, with its covered areas, was being used as a shelter for ammunition and retreating German troops. Even the Allied Military Command was convinced that enemy contingents were hiding among the ruins of the town on the slopes of Vesuvius. This is how false military information turned Pompeii and its excavations into a real target of war.

The first bombing of Pompeii took place on the night of August 24 1943, when air raids, mainly targeting the nearby town of Torre Annunziata, also affected the archaeological site. Between August 30 and the end of September, several other raids followed by both day and night. Particularly from mid-September, following their landing in Salerno on the 9th, the Allies intensified their air attacks on the whole of Campania in an attempt to consolidate their advancement and defeat the Germans.

“It was thus that from 13 to 26 September Pompeii suffered its second and more serious ordeal, battered by one or more daily attacks: during the day flying low without fear of anti-aircraft retaliation; at night with all the smoke and brightness of flares […]. During those days no fewer than 150 bombs fell within the excavation area, scattered across the site and concentrated where military targets were thought to be.” (A. Maiuri, Pompeii e la Guerra, Rassegna d’Italia 1, Milan 1946, no. 1).

On September 29 1943, Anglo-American troops finally entered Pompeii, putting an end to the bombardments and allowing the damage to be assessed.

No part of the excavations was completely spared. The areas most seriously affected include Regio VII, with Via delle Terme, Vicolo dei Soprastante, Via degli Augustali and Via Marina, and damage to the Forum and the public buildings; Regio III along the Via dell’Abbondanza, with losses to the Houses of Loreius Tiburtinus and of Venus in the Shell; Regio VI in the area between the Porta Ercolano and Porta Vesuvio and between Via delle Terme and Via Della Fortuna, with damage to the House of the Faun, the House of Sallust and the House of the Vettii. The Large Theater and the Gym were also damaged (figure). The Museum of Pompeii, founded by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1861 and renovated by Maiuri between 1926 and 1933, was perhaps the building which suffered the most damage: during the first attack it was struck by a large bomb which caused the almost complete destruction of the structure and a large part of the finds kept there, and on September 20, another bomb fell on the west side of the first room (figure).

- Regio VII, insula occidentalis bombed

- Regio VII, insula 6 bombed

At the end of the conflict, Superintendent Maiuri, himself wounded in the left foot by a bomb and having only returned to Pompeii in mid-November, reported that more than 100 buildings in the ancient city had been hit. In the lists compiled, among the rubble, the first problems mentioned are with the roofs and the upper parts of the ancient walls and frescoes. After removing the rubble and recovering the objects, a complete list of the 1378 destroyed finds was drawn up at the Antiquarium, with their description, inventory number and monetary value. The document lists fragile items such as glass and terracotta, but also objects made of bone, plaster, iron, bronze and even marble.

The damage assessment operation was followed almost immediately by the definition of the main strategies and priorities of intervention. Although the condition of the decorative elements, blown to bits by the bombs, appeared dramatic, the idea of rebuilding the structures seemed more realistic, recovering the original stones from the rubble in an attempt to duplicate the layout of pre-war Pompeii. Despite requests for economic help and equipment from the Allies, the work often came up against difficulties in the provision of materials and a lack of specialized workers. This was a period of emergency, where hasty decisions were often made to prevent further damage due to neglect adding to that caused by the war itself. One of the most remarkable outcomes is the return to the public of the New Antiquarium, opened on June 13, 1948, which was made possible in part thanks to the recovery and restoration of numerous damaged and buried finds, a patient restoration task which has seen a follow-up in recent years, with the discovery of a series of bronze objects that had been thought irretrievable and forgotten (figure).

Bombed Antiquarium

Post-war restoration often provided the opportunity to use experimental materials, such as reinforced concrete, which would later prove incompatible with the original materials, but made it possible to improve the systems and appearance of the former restorations, correcting any results deemed to be inadequate.

The events of the war and the choices made particularly in the early years of the reconstruction profoundly marked “Pompeii’s second life”, transforming forever the original appearance of the city that had emerged from the excavations up to that point and leaving a legacy of interventions that often have not stood the test of time.

Nevertheless, the experience of that phase of restoration has provided food for thought for professionals in the sector on the vital importance of treating fragile archaeological material. And the dramatic effects of war on cultural heritage, such as those occurring in the Pompeii Archaeological Park, have given rise to important regulatory initiatives, first and foremost the Hague Convention, born from the experience of the Second World War with the aim of providing tools for the defense and protection of cultural heritage, whose vulnerability in the event of conflict has unfortunately re-emerged in recent years following the dramatic events that have affected other areas of the Mediterranean, from North Africa to the Near East.

Silvia Bertesago is Archeological Officer at the Archeological Park of Pompeii