Anri Sala

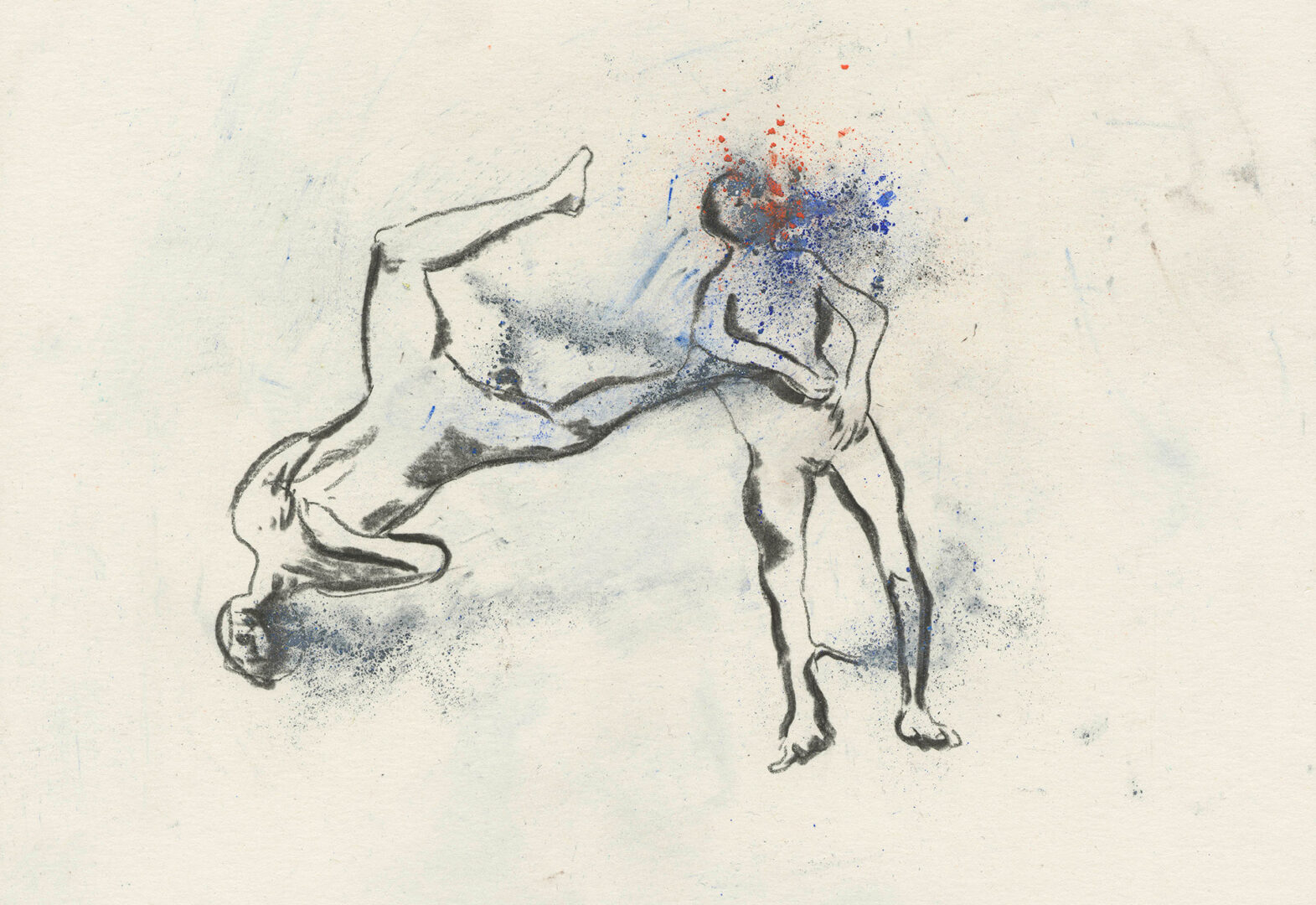

Untitled (Body Double I), 2022

pastel drawing

40 x 29,5 cm

Courtesy the Artist

Artist’s gift. Collectio Archaeological Park of Pompeii (Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters)

On Anri Sala’s Body Double. A double track between analogue and digital

(Marcella Beccaria)

Side A – The casts of victims of the Vesuvius’ eruption of 79 BC and a musical instrument of the time, but also the volume of the air, the duration of a breath, the agony of death, the emotion of discovery, the sound that breaks the silence… Where to start to write about Anri Sala’s project for Pompeii?

Since the late 90s, Anri Sala has been investigating through his practice possible models of knowledge through works capable of grafting onto the fabric of what we define as ‘real.’ Through a precise research method, each of the artist’s works poetically highlights otherwise hidden connections and human stories left out of the great history. On several occasions, Sala has drawn on the language of music and, by delving into the structure of specific tunes, he has examined episodes of possible mirroring, reworking and duplication, finding fertile inspiration in the concepts of double, similar and dissimilar.

Body Double (2022), the new work in the form of a sound track created by the artist for Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters – Digital Fellowships, was born looking at two different types of finds related to the extraordinary archaeological material given back by Pompeii. In proposing an unprecedented relationship, Sala was inspired by the plaster casts of two victims and the fragments of a tibia (aulos in ancient Greek), a doublepipe musical instrument.

Drawing on his memories from a former visit to the Pompeii archaeological site, when he was deeply impressed by the plaster casts of the victims, Sala took interest in the news concerning recent findings made in a large suburban villa in the Civita Giuliana area in autumn 2020. The discovery concerns the finding of two human skeletons and the related making of two new casts. Working with the technique originally conceived by Giuseppe Fiorelli in the second half of the 1800s, the cast plaster has given back the silhouettes of two fugitives which, together with the analysis on their bones, has allowed scholars to obtain detailed information relating to the individuals and the tragic dynamics concerning the last moments of their lives. Archaeologists have concluded that the thick ash deposit proves that the two people are victims of the second eruption of Vesuvius, the one that, in the early morning of October 25th, killed those who had survived the lava flow of the previous day. Based on the condition of their skeletons and the remains of their clothing, current studies presumably identify the victims as a young slave and his older master.

In addition to the recurrence of the number two – two fugitives stopped by the second pyroclastic flow – what struck Sala is that their bodies seem to touch, as the arm of one person is close to the foot of the other one. The dramatic circumstance, which literally unites the fates of these two individuals even more, perhaps making what is different more similar, is part of the starting point from which the artist developed his project. Sanctioning forever a relationship which could undergo even further speculation, this proximity was also interpreted by Sala through drawings on paper. Traced in grey pencil, the drawings – and it is no coincidence that the artist made two – focus on two different moments, imagined one immediately following the other. A first drawing (published together with this text) was inspired by the casts seen from above and outlines the bodies lying on the ground. As also shown by one of the documentary photographs from the excavations, the drawing shows the position of the young man with his legs extended and the one, more dishevelled, of the older man, who still seems about to contort. In the drawing, the artist insists on the point of contact, marking with a line the continuation of one body into the other. Not related to any possible photographic evidence, the other drawing imagines an earlier moment, with one of the two individuals unsteady on his legs and the other already fallen but still on his knees.

What brings together the two drawings is Sala’s decision not to focus on the presumed identity of the two individuals, their different social roles or the possible tasks they were carrying out at the moment of their escape. A series of shadings that envelop parts of the figures can in fact be interpreted in relation to the last breath taken by the victims, thus displaying the most clearly ineluctable aspect of their common humanity. These grey clouds, with red and blue dots, seem to have just exhaled from the bodies that produced them, suggesting the idea of a volume that, although feeble and invisible, nevertheless takes up space.

Together with the pair of plaster casts described above, the other finds from Pompeii on which the artist focused to develop Body Double is a tibia, a musical instrument consisting of two pipes, sometimes referred to as a ‘double flute.’ The ways in which Sala has interpreted this ancient instrument, associating its peculiar structure with the two casts, with the breath of the victims, while working on a double register, analogue and digital, also in collaboration with scholars of ancient music to produce the sound work for Pompeii Commitment. Digital Fellowship, will be the subject of the second part of this text.

RECONSTRUCTING AN ANCIENT TIBIA

(Stefan Hagel)

Even more than the lyre, the doublepipe dominated the musical soundscapes of Classical Antiquity, being the instrument of theatre productions and sacrifices as well as banqueting and dancing. When I became interested in the material basis of ancient music some twenty-five years ago, this instrument therefore demanded my prime attention. It was surrounded by some mystery and much misunderstanding. Translations almost invariably rendered both its Greek name ‘aulos’ and the Latin ‘tibia’ as ‘flute’ or ‘double flute’, although scholars had long realised it was more akin to the modern clarinet or oboe. Being played in pairs, it promised an insight into ancient ‘harmony’, which had become so important a philosophical concept. Yet, in spite of various documented archaeological finds, followed by attempts at reconstructions since the nineteenth century, little progress had been made unravelling their musical meaning. Practical attempts had been hampered by misunderstandings regarding the nature of the perished reed mouthpieces, while theoretical approaches, focusing on the placement of finger holes, had missed the technical means to predict possible scales with the necessary accuracy.

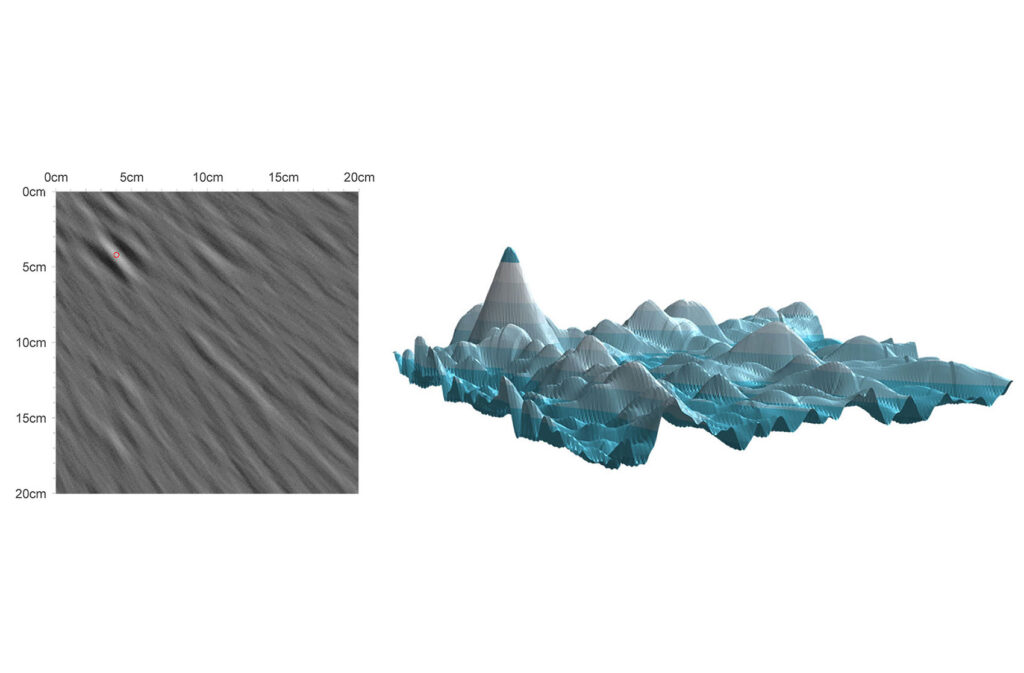

Progress, it seemed, required dedicated computer software that would establish the notes played with various mouthpieces and thus help in predicting the correct ones, maximising harmonic relations between the two pipes of a pair while remaining guided by our knowledge of ancient ‘modes’. Only very few pairs, however, had survived sufficiently intact to evaluate them without taking further unknowns into account. The most splendid of these come from excavations in Pompeii and now resides in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Their core was composed, in a traditional way, from bone sections – hence the Latin name of the instrument – and then covered in two layers of bronze and silver. The outer layer consisted of short sections that could be turned around the inner, covering and uncovering various configurations of finger holes and thus switching between modes and pitch ranges. An analysis with my newly-conceived software showed that they must have been equipped with comparative short mouthpieces, resembling those of contemporary images. Their notes thus fitted precisely within the system of Roman-period music, known mostly from melody fragments on Egyptian papyri. Would those findings survive a practical test?

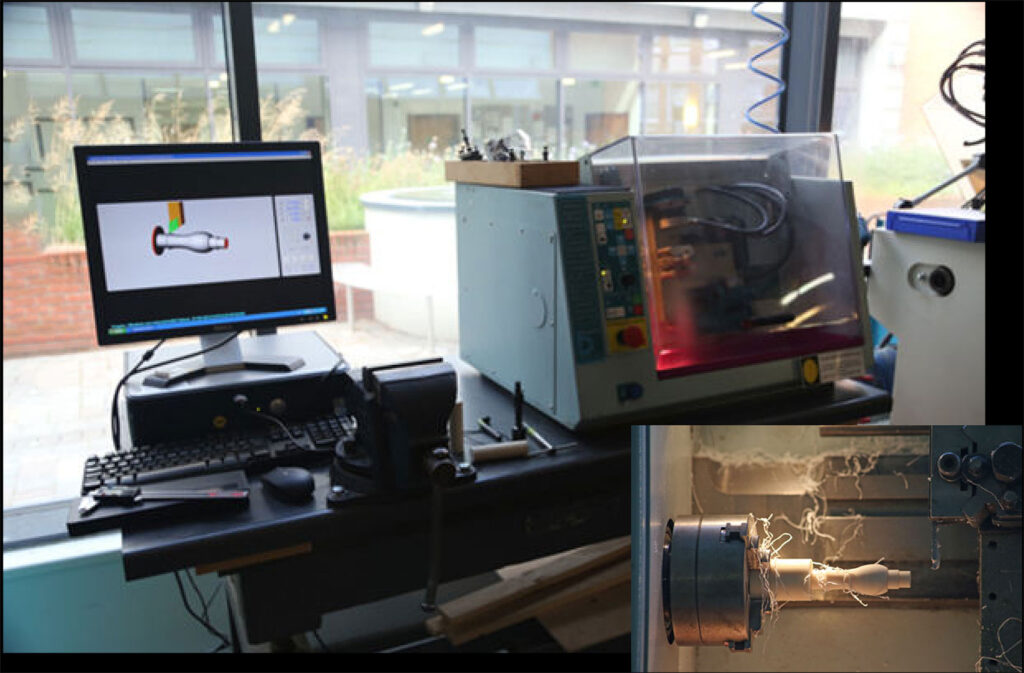

Today it is comparatively easy to produce working models of ancient doublepipes by 3D printing. Conditions were still very different when I completed my first analysis; so my first model consisted of plastic rings manually moulded around an industrially produced fibre-glass core of suitable size, to which roughly cast knobs were added for working the mechanism. But, crude as it was, it played the predicted harmonies.

Only much later, in the course of the EU-funded European Music Archaeology Project (EMAP), were we able to establish funding and collaboration for attempting a reconstruction of the metal mechanism in actual bronze and silver. At the labs of Middlesex University (London), Peter Holmes, Neil Melton and Martin Sims experimented with technologies ranging from a model of a Roman-period lathe to the most modern means of computer-driven manufacturing, finally producing a working instrument.

Meanwhile, the journey had been going on. Other aulos finds of wood and bone have been interpreted, documenting an evolution from comparatively simple instruments from the archaic period up to lavishly decorated fragments considerably postdating the evidence from Pompeii, finds hailing from much of the Roman Empire and well beyond, from Britain to Central Asia and Nubia. Nonetheless Pompeii still has musical secrets to reveal. Many of the older finds still await scientific evaluation, while a recent discovery, now housed in the Parco Archeologico, promises to shed new light on some vexed question about the music of the ancients.

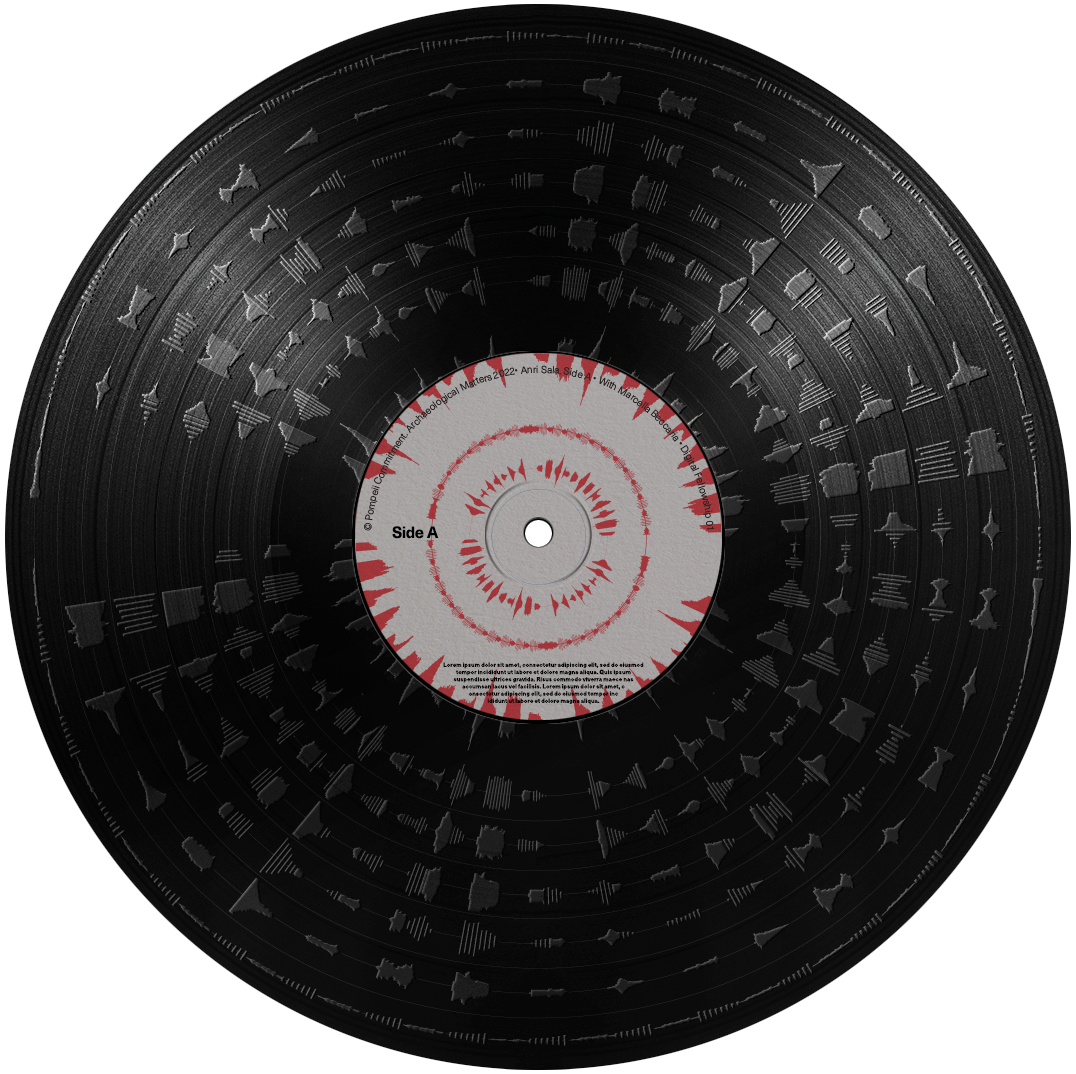

Anri Sala

Excerpt of Body Double, 2022

stereo sound, 9’25”

Music performed by Stefan Hagel

Sound design by Olivier Goinard

Courtesy the Artist

![]()

![]()

![]()