Pompeii Commitment

Anri Sala,

with Marcella Beccaria. Side A Too

Digital Fellowship 02 08•10•2022

Anri Sala

Untitled. Double Body II, 2022

pastel drawing

21 x 29,7 cm

Courtesy the Artist

ON ANRI SALA’S BODY DOUBLE. A DOUBLE TRACK BETWEEN ANALOGUE AND DIGITAL

(MARCELLA BECCARIA)

Side A and Side A Too – The casts of victims of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 BC and a musical instrument of the time, but also the volume of the air, the duration of a breath, the agony of death, the emotion of discovery, the sound that breaks the silence… There are many contents to be revealed regarding Body Double, the project by Anri Sala that inaugurates Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters – Digital Fellowships.

Since the late 1990s, Anri Sala has been investigating possible models of knowledge through works capable of grafting onto the fabric of what we define “reality.” At the basis of the artist’s works there is first of all a method, and an attention toward human events left out of the great history and otherwise hidden connections. On several occasions, Sala has drawn on the language of music and, by delving into the structure of specific tunes, he has examined episodes of possible mirroring, reworking and duplication, finding fertile inspiration in the concepts of double, similar, and dissimilar.

Conceived by the artist for Pompeii Commitment, Body Double (2022) is a new project that includes a sound track and two drawings on paper. These works were conceived looking at two different types of finds related to the extraordinary archaeological material given back by Pompeii. In proposing an unprecedented relationship, Sala was inspired by the plaster casts of two victims and the fragments of a double tibia, a double-pipe musical instrument.

Drawing on his memories of a visit to the Pompeii archaeological site which had taken place years earlier, when he saw some plaster casts of the volcano victims for the first time, Sala investigated the news concerning recent findings from a large suburban villa in the Civita Giuliana area in autumn 2020. The discovery concerns the skeletons of two individuals and the subsequent making of two new casts. Following the technique originally conceived by Giuseppe Fiorelli in the second half of the 1800s, the cast plaster has given back the silhouettes of two fugitives. The analysis of the bones has allowed scholars to obtain detailed information relating to the individuals and the tragic dynamics concerning the last moments of their lives. From the ash sediment examined, archaeologists have concluded that these are victims of the second eruption of Vesuvius, the one that, in the early morning of 25 October, killed those who had survived the lava flow of the previous day. Based on the condition of the skeletons and the remains of their clothing, current studies suggest these people could be a young slave and his older master.

In addition to the recurrence of the number two – two victims stopped by the second pyroclastic flow – what struck Sala is that the bodies seem to touch, as the arm of one of the victims is close to the foot of the other. The dramatic circumstance, which literally unites the fates of these individuals even more, perhaps making what is different more similar, is part of the starting point from which the artist developed his project. Sanctioning forever a relationship which could undergo even further speculation, this proximity was also interpreted by Sala through drawings on paper. Traced in grey pencil, these works – and it is no coincidence that the artist made two – focus on two different moments, one immediately following the other. A first drawing (published in Side A) was inspired by the casts seen from above and outlines the bodies lying on the ground. As also documented by one of the photographs from the excavations, the drawing shows the position of the young man with his legs extended and the one, more disheveled, of the older man, who still seems about to contort. In the drawing, the artist insists on the point of contact, tracing with a single line the continuation of one body into the other. Not supported by documental evidence, the second drawing (published in Side A Too) imagines a possible earlier moment, with one of the individuals unsteady on his legs and the other one already fallen yet still on his knees.

What brings together the two works on paper is Sala’s decision not to focus on the presumed identity of the two individuals, their different social roles or the possible tasks they were carrying out at the moment of their escape. A series of shadings that envelop parts of the figures can in fact be interpreted in relation to the last breath taken by the victims, thus displaying the most ineluctable aspect of their common humanity. These grey clouds, with red and blue dots, seem to have just exhaled from the bodies that produced them, suggesting the idea of a volume that, although feeble and invisible, nevertheless takes up space.

Together with the pair of plaster casts described so far, the other artefact of Pompeian origin on which the artist focused to develop Body Double is a double tibia. Already widespread in Syria and Asia Minor, this wind instrument was also known as aulos by the Greeks. Few tibiae were already found in Pompeii from the second half of the 1800s and the latest pair was found in 2018, in Via del Vesuvio. Often described as a flute, according to some scholars including Stefan Hagel (see his text published in Side A), the tibia (whose variants included the types pares, impares, duae dextrae, serranae) is actually more akin to a clarinet or an oboe, when compared to modern instruments.

Passionate about music, which is an integral part of his background, Sala has identified in the ancient instrument a found object in which the materiality of the archaeological data and the imaginative story of the myth are intertwined. As known, the aulos was allegedly invented by Athena who, according to the poet Pindar, wanted to have an instrument capable of simulating the terrifying cry of Medusa. But the goddess threw the new instrument away, because she noticed that while she was playing it she had to inflate her cheeks, an action that spoilt her beauty. The musical instrument was then picked up by Marsyas, a satyr from Phrygia who became so skilled at playing it that he believed he could challenge Apollo and his lyre. Even if the myth exists in several variants, and for the Romans the aulos becomes the tibia and Athena becomes Minerva, poor Marsyas is always condemned to a terrible destiny and his blood, as Ovid recalls in his Metamorphoses (Book VI), ends up giving birth to a river. Even if the story may lead to reflect on a possible symbolic contrast between the wind instrument’s irrational and Dionysian connotations, and the restrained and Apollonian stringed instrument, in the life of ancient Romans the tibia assumed an important role. As one can see in several pictorial and sculptural works, and from what we know about the tibicen, a specific category of professional player that included women, the instrument accompanied many moments, from banquets to religious functions, up to funeral celebrations.

Clearly, the Latin word tibia refers to the animal bone with which the instrument was often produced, even though Pliny the Elder, when describing wild trees in his encyclopaedic Naturalis Historia, tells us that the tibia was originally built using the harundo donax, a specific marsh cane thus referred to as auleticos. An in-depth study involving Pliny – also among the unfortunate victims of the eruption, and a scholar whose thought is inspiring to reread in the light of the current multispieces thought that underlies the entire Pompeii Commitment project – would lead a little too far from the primary object of this short text (and the scholars of the field are obviously more qualified to do so). However, to get to the heart of Anri Sala’s work without immediately disclosing its contents, allow me to quote a few lines from the Naturalis Historia. In addition to explaining that the cane was a material that was later abandoned due to the very long aging and processing times that it required, Pliny reports that, when still used to make the musical instrument, they were cut when ripe. He then adds:

“Thus predisposed, they started being usable after a few years, and even then they had to undergo a long training: in short, it was necessary to teach the flutes themselves how to play, otherwise the reeds would remain tight, a feature more suitable for use in the theatrical representations of the time. After the variation and the splendor of singing were introduced into the music, the canes were cut before the solstice and were used after three years, when the more open reeds allowed to modulate the sounds. This is how flutes are crafted to this day. But at that time, it was believed that the reed would fit well only if it came from the same cane, and that the part above the root was suitable for the left flute, while the part towards the top was good for the right flute; the canes grown on the banks of the Cephissus were highly praised. Nowadays, Etruscan flutes for religious sacrifices are made of boxwood, while those for celebrations are made of lotus wood, donkey bone, or silver.”

Among the precious information and concepts it contains, for the non-specialists, this quote from Pliny can help to better understand that the sound of the tibia was produced by the player by holding the two pipe elements in his/her mouth and making the reeds vibrate, while fingering the holes on them. Another interesting point is the differencing mentioned by the scholar between the left and right flutes.

In the context of Anri Sala’s project, what intrigues me above all is the concept expressed by Pliny at the beginning of the paragraph quoted above, where he writes that “in short, it was necessary to teach the flutes themselves how to play.” I am tempted to think that this statement could be streatched up to the world that obsesses us so much nowadays, that of artificial intelligence, with “intelligent” machines capable of learning from themselves. Although risking a dangerous encroachment in “alternate history,” which certainly does not belong to the vast areas investigated by Pompeii Commitment, I address this aspect because it is out of the question that the contribution of the most current technologies was crucial in the evolution of Body Double. Attracted to the ancient musical instrument, the artist had to face the fact that it was not possibile for him to handle it, or to have it loaned to a musician who could collaborate with him by playing it for the project. As the scholars who take care of the Pompeii heritage so well know, the various tibiae recovered on the site over time are very fragile finds, and it is not possible to interact with them outside of special protocols.

Yet, the artist’s desire to revive the sound of a Pompeian tibia has become a reality. After some research, that revealed the multiple activities of a lively international community of scholars of ancient musical instruments, Sala came into contact with the aforementioned Stefan Hagel. Through years of meticulous study and multiple empirical attempts, Hagel has in fact come to create a working copy of the ancient instrument, which he himself plays by applying his knowledge as a passionate and rigorous researcher. Obtained from the precise measurement of a pair of tibiae found in Pompeii in 1867 and now preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Naples, the reproduction was created by the scholar thanks to digital technology, which allowed him to get a 3D print to work on.

Although already articulated, this is however only part of the story of Anri Sala’s project. In fact, there is much more to say about the ways in which, in the artist’s creative imagination, the tibiae and the casts of the victims came together, and about the specific structure of the musical piece produced by the artist. As for the first point, from the very beginning of the project the artist looked at the casts and the tibiae as if they were linked by a sort of inner necessity. As mentioned, he was struck by the fact that the second eruption had joined forever the two victims and he was drawn to the ancient wind instrument made up of two elements. Sala explored this unprecedented relationship according to the concept of double – but also of similar and dissimilar – questioning the possibility of developing a further aspect, i.e. the one between the space occupied by the bodies and the duration of the sound coming from the tibiae (or a faithful copy of the instrument). This relation, in which space corresponds to the void found within the ash, led Sala to develop the sound work, an artistic response based on a mathematical intuition. One of the fundamental elements of Body Double is in fact its duration, which can be interpreted as the digital transformation of an analogue datum. The 9.25-minute duration of the piece comes in fact from calculating the time it takes for the volume of air left by the bodies – and then defined by each of the plaster casts – to flow through a tibia when played by a musician’s breath.

This translation of a space volume into a duration, sculpts the sound space. To finally get to at least mention the structure of Body Double, it is important to mention that it was constructed by the artist in collaboration with the sound designer Olivier Goinard, thinking of the image of two human lungs and combining a sequence of breathing phases and musical notes played by Hagel using his instrument. The technique used by Hagel includes the so-called “circular breathing.” Know to different cultures and essential for playing the tibia, this technique allows not to interrupt the sound flow when breathing, as the musician constantly blows the air into the instrument, while inhaling air from his nostrils. As for the tones, which could perhaps recall ship sirens, they are based on the “third tone,” an acoustic phenomenon that arises from the combination of two tones which, when produced simultaneously, in turn produce a further tone. Also called ‘resultant tone’ or ‘combination tone’ (and described for the first time by the Italian violinist Giuseppe Tartini in his Treatise on Music According to the True Science of Harmony, 1754), the third tone represents an illusion but is at the same time real. Recognizable by the human ear, whose structure contributes to its production, it has frequencies mathematically associated with those of the tones from which it derives.

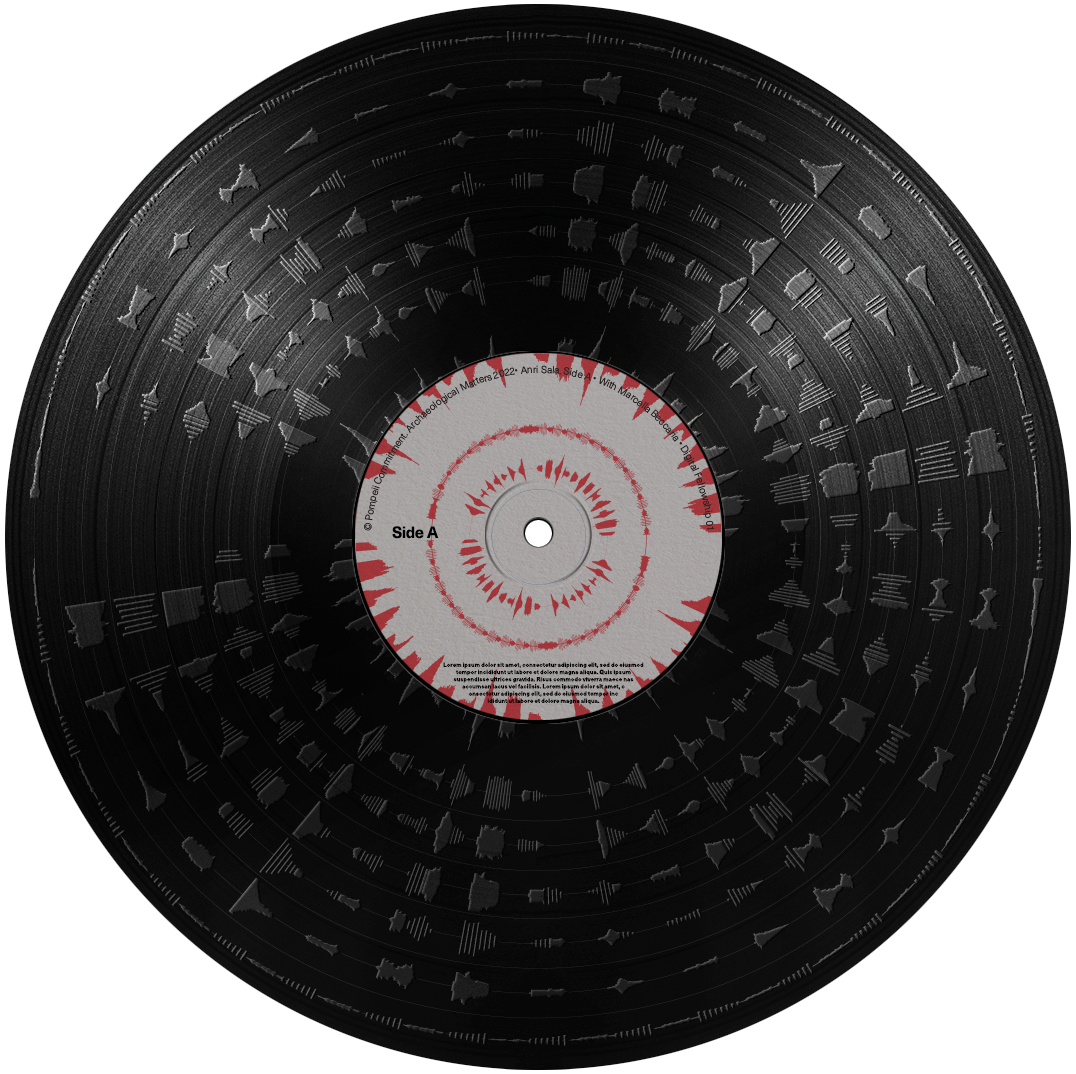

In order not to deprive those who will experience Body Double of the emotion of the encounter, I would not add anything else here, except that the ‘analogue vinyl’ inspiration for the design of this digital project is obviously intentional. An elegy dedicated to the victims of Pompeii, the work lingers on their last moments, and on the human meaning of the void they left forever imprinted in the ashes.

The author would like to thank the Artist and his Studio, Linda Fossati, Alessandro Russo and the curatorial team of Pompeii Commitment. Archaeological Matters

Anri Sala

Body Double, 2022

stereo sound, 9’25”

Music performed by Stefan Hagel

Sound design by Olivier Goinard

Courtesy the Artist