Pompeii Commitment

Simone Fattal. Pompeii, Today

Commitments 05 21•01•2021Pompeii, Today.

It took centuries to start looking at Pompeii again.

But the word, the event was forever present in the imagination of people around the world.

Although forgotten, when it was “rediscovered” everyone knew what it was about.

For the destruction of Pompeii left a scar on everyone’s imagination.

Why?

Pompeii represents what the word destiny signifies.

Something happens that comes from nowhere, and cannot be stopped.

An event that concerns all and that no one can escape.

It took years to start unearthing the site. But each time something was unearthed, people were confronted with what it means to be facing an instant, in destiny.

Unlike all the other archaeological sites, we can say that Pompeii gives a reconstruction in itself. For the place has not been destroyed by time, but by a moment.

The place is frozen in that instant. And the destruction preserved it.

Another irony.

Protected by the lava and debris, it was not looted and disappeared during the centuries, and when it reappeared, it reappeared intact. One by one the monuments emerged, as they were on that day.

♠

Today November 22, 2020, I read in this fleeting news on one’s telephone: two new corpses found in Pompeii…

♠

In 79 AD, the whole city of Pompeii, was struck with an explosion, we can today qualify it as a nuclear explosion, that destroyed the city entirely in a matter of hours, or two to three days.

They heard the rumble and the noise, the earth was stirring and moaning like never before. No one understood what was going on and what was to happen.

One eminent woman, important enough to send an emissary in the first hours of the uncertainty and fears that were settling, of the incomprehensible but dangerous enough to worry signs – I repeat, she sent an emissary to Pliny the Elder, who was the prefect of the Fleet, posted nearby in Casties –, for him to come and rescue her. Although he started immediately, he did not make it, but died on the way, probably from a heart attack due to the fumes and other dangerous materials – and she died too.

♠

Death took different forms.

Was it destroyed in one instant? No, but what we see is an instant.

A moment in time, a moment in history as we can never witness anywhere else. An instant frozen for eternity. An instant comprising everything.

The life of a city. Its houses, monuments, temples, everything is there, as it was, from the same day. As if it has been photographed that day.

People were caught doing their daily routine.

Or trying to escape.

We can witness the fear, the despair. The surrendering.

We can also witness their civilization as a whole.

This also is rare.

Ruins in the world can be read on many levels, but there are fragments of all periods mingled together, or on top of each other; you have to reconstruct the influences, the sequence in time. In Pompeii, it’s a fixed image.

♠

I started discovering Pompeii by visiting the Naples Archeological Museum.

The first thing which struck me was the paintings. They on the whole express happiness.

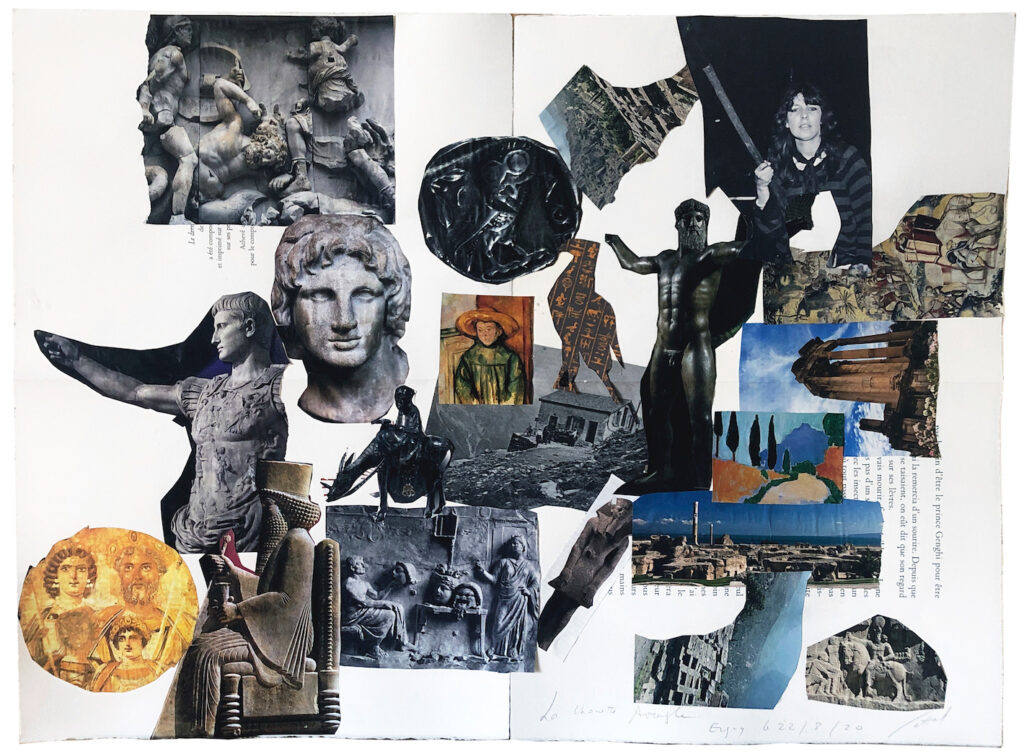

These paintings, which to me prefigure the paintings of the Renaissance, reflect harmony, peace, and a joie de vivre. Women, plants, flowers, music, myths.

Therefore, we can say that the Pompeii society, rich, diverse, enjoyed a happy life. They were trading with all the harbors and cities of the Mediterranean.

By the sea, but surrounded with fertile land, wine and olives and cereals, fruit, were their produce and environment.

A port, open to all trades and commerce; open to all civilizations, all the influences. Different people from around the Mediterranean came to Pompeii, established commerce.

Sailors, merchants.

They also established temples, customs.

There was a pollination of all these different cultures.

Gods and goddesses from around the Mediterranean.

Their customs came and stayed, their artifacts also.

There was a political life, and we see and read electoral slogans.

A cosmopolitan city. A happy one.

We see an unusual number of houses that belonged to freed slaves. The theory is that a number of rich people had already left the city after the last earthquake, and that they had sold their houses to the freed slaves.

Carefree and modern.

We witness a sexual freedom, political diversity, ethnic diversity.

And the importance of rich and wealthy women in their own right, who owned their houses and businesses – as the example given above indicates.

Actually we witness the way of life.

Egypt is present, but also Syria, and Asia Minor. But with all this diversity and differences, it seems that all lived together in harmony.

It can certainly be a model for today.

Today all major European cities have also a fantastically varied population, but that seems to create major problems. On the contrary, it does not look as if they had a minorities problem.

The art was Pompeian, i.e. Roman, i.e. Italian.

and as I said already, it will make its way to the Renaissance.

The temples are there but also the houses.

And in them everything was left: utensils for cooking, pets, jewelry, beads, charms, art collections. These houses were patricians, they belonged to rather rich people who collected sculptures, and adorned their walls with paintings.

Life in its richness and variety was caught for us all to see and admire.

No other city in ancient history will give itself to the world, so much, so well and without artifice.

♠

Rich and varied, opulent and bustling with life, Pompeii is also synonymous of death.

This is the lesson we hear: Death is with us and cannot be fought.

We just have witnessed another similar nuclear explosion on August 4 of this year in Lebanon.

At 6pm, death struck and struck violently. The whole city was not erased, but a city the size of Pompeii was “blown away” as in Hiroshima. Buildings and streets evaporated. Deaths and wounded abound.

It was not Mother Earth, growling from the depths of its entrails, but the evil hand of evil.

Two opposite events.

♠

This brings me to my sculpture.

My sculpture tries to recapture the living element of the fleeting moment that brought death.

My sculpture wants these moments to live eternally, being close to the spirit of the place and day, and give them back to life.

But what would I do if I were committed to make an artwork or an exhibition in Pompeii?

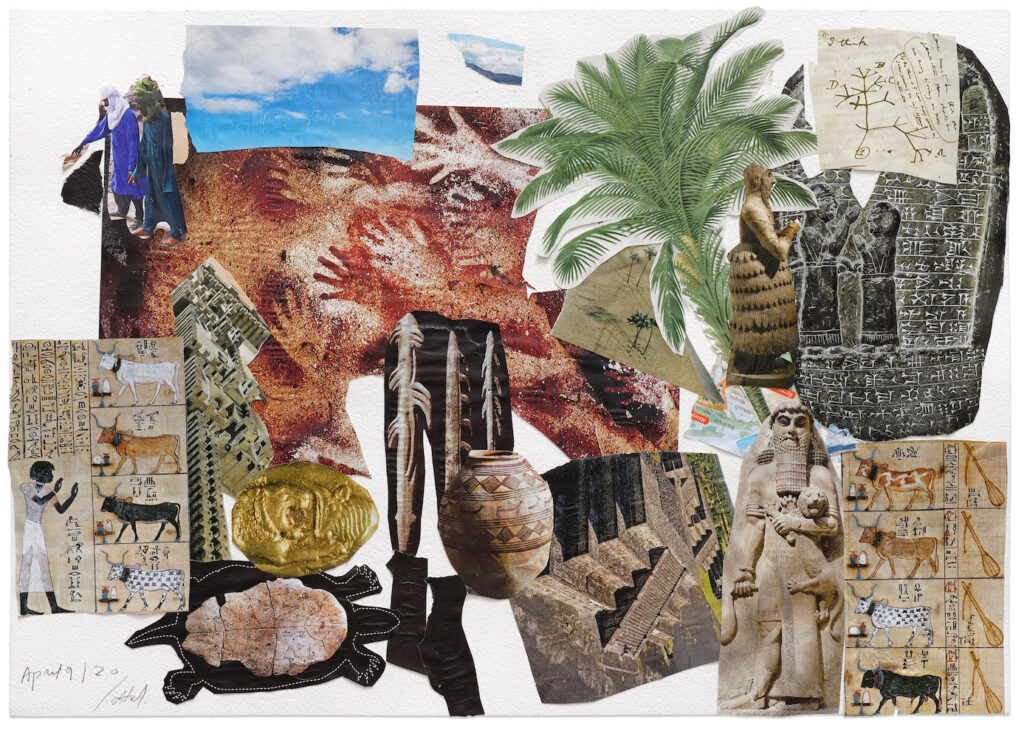

I would start with identifying its place in the Mediterranean.

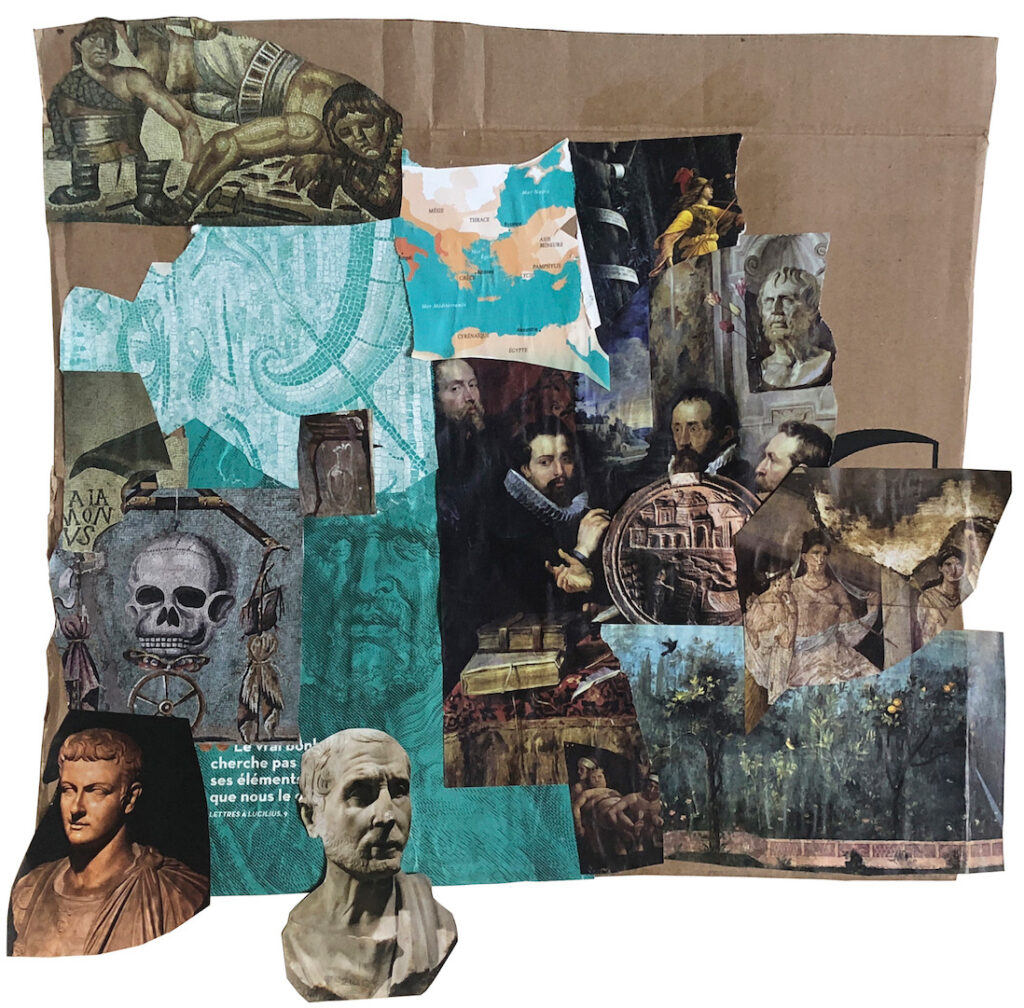

One should, everyone should read The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon. I read it because I know that the Roman Empire is mainly Syria, Egypt, Asia Minor, North Africa. The Roman Empire went also westward all the way to Britain, but the intense pollination and lasting effect was in the Mediterranean.

Started with the Hellenization brought to the Orient by Alexander the Great and his generals, it continued without any hiatus with the advent of Rome.

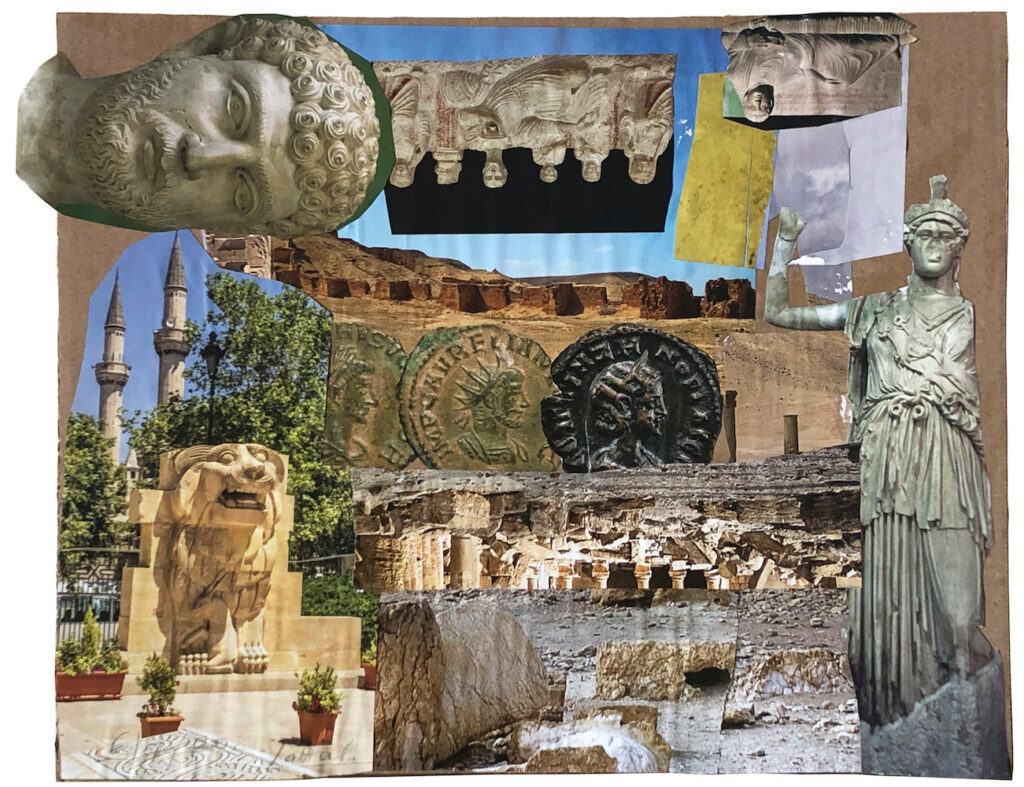

This is where the osmosis and the Roman civilization flourished and lasted the longer. This is where the largest examples of Roman architecture, interpreted by the Orient, took place: Baalbeck, Palmyra, Basra Iskisham, Carthage…

When I first arrived at the Naples airport in February last year, a bit before the pandemic started, I noticed a magnificent replica of a Hermes sculpture.

He would be the first I am going to portray in my installation.

That day Hermes did not make it on time to warn the citizens of Pompeii of the imminent danger.

Then I would portray Isis at the bed of her father, trying to get from him, as he is sick, all the secrets of his power.

She will succeed.

And last but not least, many persons depicted on the walls of the House of Mysteries.

Why the House of Mysteries? Because there you read on the walls the story of the initiation of women to the rites of passage from girlhood to womanhood.

To the mysteries and rites of death.

The life cycles.

To finish by a monumental figure of Anubis, as he is painted on the walls of that house.

Anubis the guardian of death.

I would not finish on this note, but on a triumphant, beautiful (I hope) rendering of Apollo.

The God Apollo, God of music, love, and power.

Like Isis, he is portrayed with a lyre in his hand.

One icon facing the other.

Simone Fattal